|

FBYC History.... Jere Dennison Way back in 2005, your Historian dealt with the uncomfortable topic of a dispute between FBYC and its then immediate neighbor to the west, Edith Hancock, during the late 1960s. Aficionados of club history (of which, I am assured, are legion) will recall (or will read the original Opportunity Lost article posted in the history section of the club website) that this kerfuffle resulted in the dismantling of a portion of the western T-section of the Fishing Bay pier in 1967 and the failure two years later in 1969 to acquire the Hancock property next door during a period of club physical expansion. Probably little noticed by club members in the June 21, 2012 of the Southside Sentinel (published weekly in Urbanna) was a front-page article that sheds more light on this regrettable incident in our history. The article highlights the career feat of distinguished Saluda attorney, Roger Hopper, to have argued 11 cases before the Virginia Supreme Court, the first of which involved – amazingly - the Hancock-FBYC dispute. Imagine…who would believe that our humble and friendly little yacht club would actually be hauled before the State Supreme Court kicking and screaming to resolve a civil dispute? But, yes, it did happen, and an insider’s perspective of this judicial action is excerpted and reprinted below: “No Stranger to the Supreme Court” Saluda attorney Roger Hopper has argued 11 cases before the Virginia Supreme Court – an unusual feat itself – and what’s even more remarkable is that he recently won his eighth of these cases. “Most attorneys in the state never go before the Supreme Court,” said Hopper this week. “There are attorneys employed by Dominion Virginia Power or the phone companies who often go before the court, but most country attorneys never try a case in Virginia’s highest court.” Part of Hopper’s success in the Supreme Court goes back to his first case in 1967, which laid the foundation for several other riparian rights cases. In his first case Hopper represented an elderly lady, Edith D. Hancock, and the then predominantly Richmond-based membership of Fishing Bay Yacht Club in Deltaville. In 1967, the club decided to expand its Fishing Bay pier by enlarging the “T” at the end of the pier to accommodate an increasing number of cruising yachts and additional sailing activities. After the pier construction had been completed, Mrs. Hancock filed a lawsuit to force the club to remove the new section of the pier, which she said encroached upon her oyster grounds. Furthermore, she would not agree to a settlement with the club that would permit the pier to remain intact. Hopper argued that the state had properly laid off Mrs. Hancock’s statutory riparian half-acre, while the yacht club’s attorneys argued otherwise. Hopper first represented Mrs. Hancock in Middlesex Circuit Court where Judge John DeHardit said, “This case sort of reminds me of the words used in a burial service (Book of Common Prayer). ‘The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. In this particular case the State giveth and only the State can taketh away.’” The Supreme Court justices agreed with Judge DeHardit and on April 24, 1967 Hopper won his first case in the state’s highest court. “I can remember the day well that they were scheduled to cut off the pier and pump up the pilings,” he said. “Mrs. Hancock and I sat on her front porch and watched while she served gimlets” (a gin and lime juice drink).

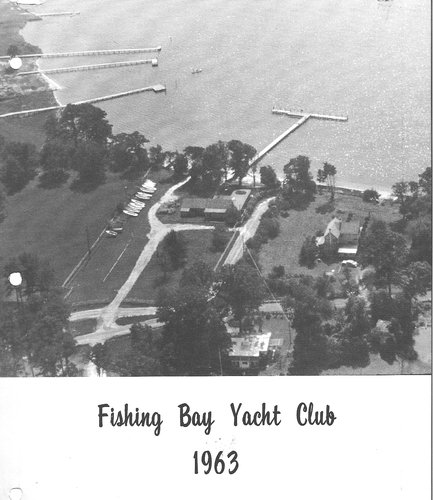

At closing, the club syndicate was infuriated to learn that Mrs. Hancock intended to transfer title to the property without the controversial oyster rights that had eliminated the ‘T’ extension at the end of the pier. Indignantly, and in an ultimately self-defeating effort to get even, they refused to consummate the purchase. Such was the animosity created by the 1967 litigation that the Club would abandon the effort to acquire the Hancock property for so insignificant an issue while totally ignoring the obvious strategic benefits that would have accrued in its purchase. However, every cloud has a silver lining. I was later mortified to learn from a close friend of mine whose father was a member of the syndicate that the secret plan for the property was to bulldoze the quintessential old tidewater farmhouse (now owned by the Ralston family) once the acquisition had been completed. Of course, Mrs. Hancock would never have agreed to the contract in the first place if she had known that her beloved house would have been demolished. And the area would have lost a lot of the character that we now enjoy so much around our club. The nearby aerial photo of FBYC and the Hancock property from the cover of our 1963 handbook clearly denotes the relationship between the two properties at the time and illustrates the Fishing Bay pier before the infamous ‘T’ extension was added later in the decade. Mrs. Hancock’s big, old lumbering Buick sits in the driveway behind her house, and her Chicken Coop, moved earlier from the Stull property and transformed by her into two cottage rental units, is shown at the bottom of the picture. Our Fannie House replaced the Chicken Coop in 1997. ### |

Aftermath:

Aftermath: