Rememberance of Mac McCullough - by Ken Ringle

on Tuesday May 20, 2003 09:18PM

Alan McCullough, Jr. was a FBYC member most of his life. He died May 11, and his memorial service on Friday was attended by his family and many friends. Among the rememberances read at the service was the following article, which was written and read by Ken Ringle.

Alan McCullough, Jr. was a FBYC member most of his life. He died May 11, and his memorial service on Friday was attended by his family and many friends. Among the rememberances read at the service was the following article, which was written and read by Ken Ringle.

As most of us know, Mac made a movie about his life. No film was actually shot, of course, but that is somehow beside the point. The movie was always showing on the inside of Mac's forehead.

What made relations with Mac so maddening, so bewildering and so much fun-all at the same time-was that he was always simultaneously shooting the movie and watching it. And directing it. And editing it. And starring in it. And narrating it. And laughing at it. And, of course, critiquing it, even as he was talking to you.Even if there were only two of you, Mac was always carrying on about five conversations and-at the same time-laughing uproariously at the one in the movie he wanted you to know was so real to him he was almost overhearing it.

In any other person this would be the very definition of psychosis. Yet in Mac it was a unique recipe for the art of living. He remains, at heart, one of the deepest, one of the brightest and one of the sanest people I've ever known.

As some of you know, we were joint occupants with Alfred Scott of the Thomas Milton Arrasmith home for arrested adolescent males. It was located at 2425 Grove Avenue in Richmond during 1969 and 1970, two fairly flamboyant years in the life of this Republic. I realize much of the world was in turmoil then, what with racial strife, Richard Nixon and Vietnam, but I remember those years today as ones of almost unalloyed delight. All the days shine in memory as sunny and cloudless, the grass eternally green, the trees and flowers forever in bloom. I remember the Beatles instructing us repeatedly "not to make it bad/To take a sad song and make it better/Remember to let her into your heart/And you will start/To make it better."

We took that advice very seriously. I was emerging from a 10-year marriage like a groundhog coming out of his burrow after hibernation, so I sought advice from Mac on how to handle my new life.

"You must live life as a tragicomic figure," he said. "If you're a comic figure, women will never take you seriously. If you're a tragic figure you'll just depress them. But if you're a tragicomic figure you'll amuse them, they'll like you and want to protect and mother you, but they won't expect a whole lot from you. And you'll remain free to live life on your own terms."

I didn't realize at the time that Mac was describing not just his approach to women but his approach to life. Whether the philosophy became before the lifestyle or vice versa is hard to say. But the director of a movie is always conscious of what he's putting on film, whether he scripts it beforehand or makes it up as he goes along.

The genius of Mac's life film was its resilient, uncrushable humanity. He insisted he was paranoid, and kept a loaded shotgun under his bed at Grove Avenue against a variety of conspirators he insisted haunted his dreams. He would tell us the blacks were coming to get him, then spend all day playing checkers with black George in the elevator shaft of his apartment building near VCU. He would tell us the Russians were coming to get him, then fall asleep between two enormous stereo speakers thundering songs by the Red Army Chorus. He spent months as a real estate agent looking for a house for Arrasmith to buy, then went off sailing while Arrow found the Grove Street house on his own. When Tom apologized for leaving Mac without a commission, Mac said "That's all right. I need a place to live" and promptly moved in.

He was somehow a willing co-conspirator in all the tricks we played on him. Like the famous Donald Duck nightlight we snuck into his bedroom the night he was bent on entertaining some VCU coed. Just as he turned out the lights, she shrieked "WHAT'S THAT!!" and began laughing hysterically. Mac, with his glasses off, was even blinder than I am without my contacts. He denied he had any sort of nightlight, much less a Donald Duck nightlight. The explanations went on and on while we eavesdropped outside in convulsions. He later protested gleefully that the only real problem was that we had unhinged his tragicomic balance and reduced him to comedy alone.

He was furious, on the one Christmas he finished his shopping and wrapping early, when Arrasmith's golden retriever invited himself into Mac's apartment, tore open all the presents under the tree and left Mac a different sort of Christmas present on the living room rug. But he soon had both us and himself in hysterics imitating Woof's Christmas morning pursuit of a particular, wrapping-stripped robotic toy.

It was Alfred who brought home the unicycle, but it was Mac who turned our futile efforts to ride the thing into some sort of hilarious, ankle-bleeding competition. We'd come home after work to find him outside in freezing weather balanced between two parked cars, propped up on the unicycle in an overcoat, trying to sneak an edge in training.

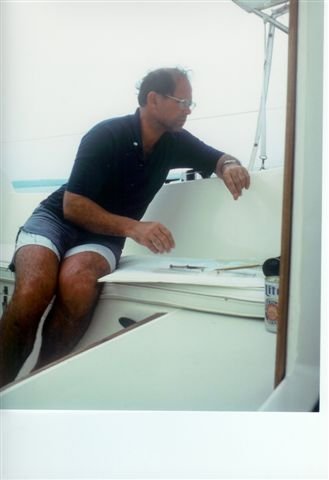

In 1979, while bringing the McCullough O'Day 37 "Mary" back from Florida, Mac and I were asleep in the forepeak when his father awakened us at 4:30 a.m. with the sort of gentlemanly skipper command I always associate with Captain Al: "Excuse me, boys. I hate to wake you but I'm afraid we're going to need you on deck. The wind's up over 30 knots, the Loran's gone out and a big squall line's blowing us down on Frying Pan Shoals. I've never brought this boat about in seas like this, and I don't know just how she'll behave. So I think maybe we ought to shorten sail."

Soon Mac and I were crouched on the pitching bow horsing the jib down while waves hissed out of the darkness and broke over us. This was my first ocean storm and both my heart and my dinner were in my mouth. I looked to Mac for some clue on how to handle all this. He looked up at me with that manic, gap-toothed grin of his and said gleefully "Hey, this is the way it really WAS!"

For the next couple of days we tacked back and forth off Cape Fear as the storm blew itself out. Mac instructed me in the tragicomic view of life offshore. Instead of psyching ourselves guessing how big the waves might be, we used the fathometer to compute the difference between the depth on the crest and the depth in the trough. That came to 18 to 20 feet. Then Mac decided to cast the different types of waves in his movie by naming them after NFL linebackers. The big green-water breakers were Mean Joe Green waves. The ones that broke before they got to us and were all white and hairy were Ben Davidson waves. And the ones that were dark and menacing and bald on top were Otis Sistrunk waves. Mac was the calmest fellow on the boat.

In recent years he would call me regularly in Washington to talk, announcing himself as "This is Erwin Rommel. I have just discovered I'm allergic to desert sand." Or "This is Hans Guderian. Vill you pleez put zoz Panzer divisions back where they belong? I tell you, zere is nossing going ON in Normandy!" Huh-Huh-Huh. Or "This Marshall Zhukov. I would like to remind you comrades that the name of this city is STALINgrad." Huh-Huh-Huh. Or he would call in the middle of the night, fresh from his history books, and say "Did you realize if just 20 more T34 tanks had been disabled, the Battle of Kursk would have turned out completely differently?"

When Mac found out he had cancer he called me up and informed me with a kind of detachment. He clearly understood that this was the last scene in the movie, but he wasn't going to have it be a tragedy. He made prostate gland jokes, but he also spoke with a kind of benedictive calm and dignity. Last summer I had some business in Richmond, and we met for lunch at the Jefferson Hotel with the wonderful Jennifer, whom he told me he was tutoring in all the history she should have gotten in school but hadn't. He was his old self with his bow ties and his grins and his laughter. When he went to the john, I asked Jennifer how he really was. She said there were good days and bad days. He never called me on a bad day. At least not for me.

He called me regularly until about two months ago. He wanted to talk about Iraq and about a story assignment that had taken me to the Persian Gulf, and he said he planned to get Jennifer to drive him up to Washington and take Arrasmith and me out to dinner. I told him to come stay with me, but he said no, he wanted a good hotel with a great restaurant downstairs. That way, he said, "You all can keep eating while every now and then I find the need to go upstairs to my room, close the door and scream in agony. Then everything's fine and I can come back down and have a few more drinks. Huh-Huh-Huh."

He helped me fool myself into thinking there was much more time. When you're watching a movie you really love, you lose track of how long it's running. And a really great director of tragicomedy keeps you laughing and crying at the same time, right up to the end.

Obituary in Richmond Times-Dispatch

Alan McCullough Jr. of White Stone, Virginia, died on May 11, 2003. The son of Alan and Mary Winston McCullough, Mac was born in Norfolk, Virginia on January 5, 1942. He graduated from St. Christophers School in Richmond and Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y. Mac was a real estate broker in and around Richmond for many years. In recent years, he lived in White Stone, Virginia. He is survived by his brother, Francis "Frank" Wheatley McCullough II; two sisters, Jane McCullough Wells and Lucy McCullough Schneider; three nieces, Mary Winston Nicklin, Emmy Nicklin and Julia Schneider; and one nephew, Sam Pretlow Schneider. A memorial service will be held at his White Stone residence at 11 a.m. on Friday, May 16. Memorial donations may be made to St. Christophers School at 801 Henri Road, Richmond, Virginia 23226 or The Chesapeake Academy, 107 Steamboat Road, Irvington, Va. 22480.

Alan McCullough Jr. of White Stone, Virginia, died on May 11, 2003. The son of Alan and Mary Winston McCullough, Mac was born in Norfolk, Virginia on January 5, 1942. He graduated from St. Christophers School in Richmond and Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y. Mac was a real estate broker in and around Richmond for many years. In recent years, he lived in White Stone, Virginia. He is survived by his brother, Francis "Frank" Wheatley McCullough II; two sisters, Jane McCullough Wells and Lucy McCullough Schneider; three nieces, Mary Winston Nicklin, Emmy Nicklin and Julia Schneider; and one nephew, Sam Pretlow Schneider. A memorial service will be held at his White Stone residence at 11 a.m. on Friday, May 16. Memorial donations may be made to St. Christophers School at 801 Henri Road, Richmond, Virginia 23226 or The Chesapeake Academy, 107 Steamboat Road, Irvington, Va. 22480.

Published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch from 5/13/2003 - 5/14/2003.